Pennies to Dollars: The Problems With Amazon’s Plans for Detroit

Local officials have not been transparent in dealing with the tech and retail giant or its partners, to the detriment of the area’s people

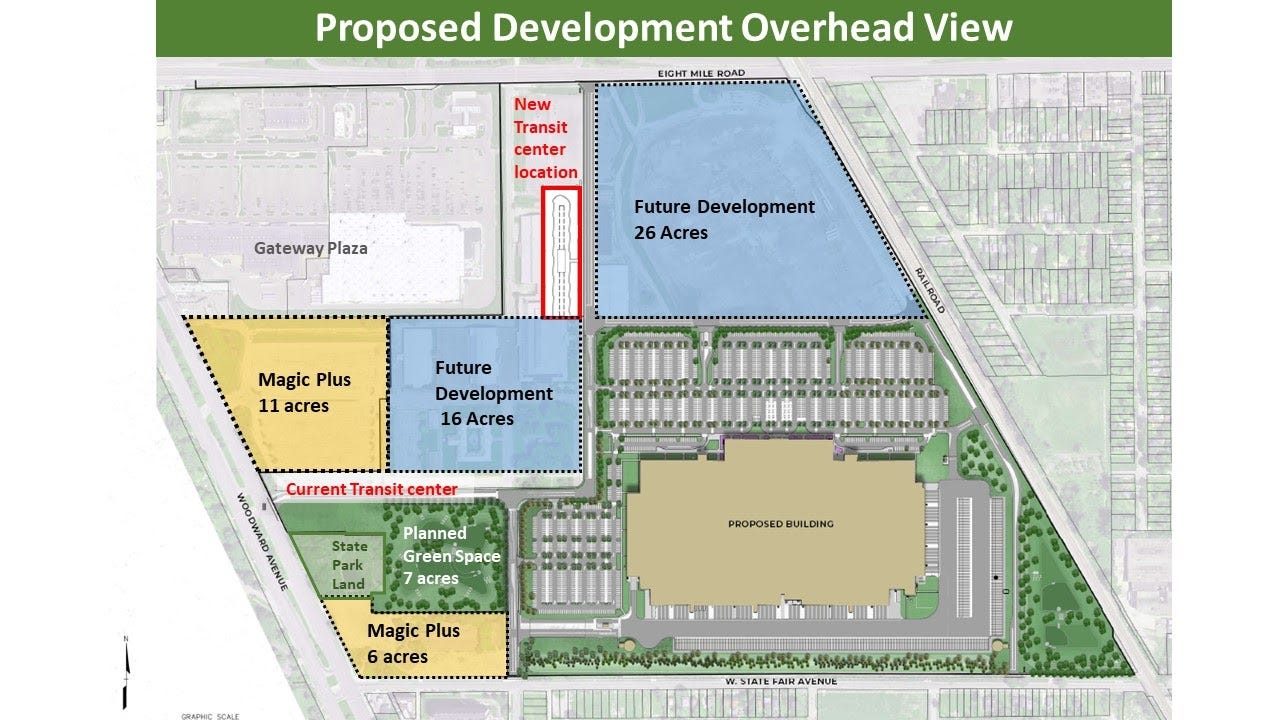

An artist’s rendering of the transit center that will be part of the Amazon complex at Detroit’s State Fairgrounds site. Courtesy the City of Detroit.

I have had another story planned for Wednesday for a while, and I’m still going ahead with that. Now, though, I want to write about something that just happened, but turns out to have been brewing for years, and which sheds some light on Amazon’s dealings with local politicians and developers. The last time this side of Amazon’s business made big-time waves was when Amazon first selected, then chose to walk away from the city of New York after strong opposition to its plans to build a second campus there. I wrote about it almost two years ago, in this newsletter’s early days. Anyways, what’s happening in Detroit right now repeats many of the same things that caused Amazon so many problems back then. The biggest differences are the sheer numbers and the fact that I don’t expect there to be much of a fuss, except from a few very pissed-off Detroiters. Of which (raises hand) I’m one, right here.

So what’s going on?

Early on January 11, Amazon issued a press release announcing the totality of its plans to expand its footprint in Detroit, both in the city and its suburbs.

"We're thrilled that Amazon selected Detroit for what will be one of the largest fulfillment centers in Michigan,” said Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan. “Amazon has been a great partner and its most important delivery will be the 3,000 construction jobs, 1,200 permanent jobs and new small business opportunities this new facility will bring to our city."

In all, Amazon is constructing six new facilities on five different sites in and around Detroit.

Detroit – Amazon Robotics Fulfillment Center.

Hazel Park – Sub-Same-Day Fulfillment Center.

Pinnacle Park – Amazon “XLFC” Fulfillment Center.

Pinnacle Park – Amazon Sort Center.

Plymouth – Amazon Sort Center.

Pontiac – Amazon Robotics Fulfillment Center.

The big facilities are in Detroit and Pontiac, on the site of the former State Fairgrounds in Detroit and the Pontiac Silverdome (former home of the Detroit Lions and Wrestlemania III), respectively. But these deals have been known for months by people who follow Amazon or who live in the Detroit area; there have even been preliminary but public announcements of them both, and (in the case of the State Fairgrounds site), a series of community protests and a lawsuit that at one point looked like it might halt development of that facility altogether. With this announcement, Amazon seems to be signaling that it’s in the clear and is moving full-speed to get these buildings going ASAP.

The real news for me is about the Pinnacle Park site. It was briefly the site of a thoroughbred horse racetrack in Huron Township, just west of the city, not far from Detroit’s massive Metropolitan Airport. The racetrack failed, and the property reverted to Wayne County, who have been struggling to figure out just what to do with it.

“With this deal, we are able to appropriately redevelop the Pinnacle property – adding roughly 1,000 new jobs for local residents while expanding our tax base at the same time,” said Wayne County Executive Warren Evans. “When I took office, I made it a priority to repurpose the land in a more productive way that made sense for the location. Working in collaboration with Huron Township leaders and Detroit Aerotropolis, my team identified a new approach for the site that was both economically viable and consistent with the community’s vision. I’m pleased that Amazon agrees that Pinnacle is a prime location for a world-class logistics and distribution facility that will put Wayne County residents to work.”

(Note: “Aerotropolis” is a bullshit word people have started using to make it seem like having a big airport is just as important as having a thriving local economy. Detroit’s officials aren’t alone in this, but god, they have bought into it so hard.)

So just what the hell happened to Pinnacle Park, and why is Amazon suddenly in a position to develop an “XLFC” there?

Wait, first of all: What’s an XLFC?

Is that some new filthy internet slang?

Should it be?

An aside about Amazon’s shipping facilities: I had never seen the term “XLFC” before used by Amazon; “FC” for “Fulfillment Center” is common, but “XLFC” is new. According to an Amazon spokesman, an XLFC is indeed an Extra Large Fulfillment Center, and it fulfills larger products: television sets, patio furniture, and other things that require team lifting, specialized carts, and sometimes forklifts to move. This is a new kind of fulfillment center: sometimes Amazon refers to “nonsorting fulfillment centers” that often handle larger items, but this is different. We can probably expect more XLFCs to start popping up elsewhere in Amazon’s fulfillment zone, first in the US, then everywhere.

The Pinnacle Park site will also host a sorting center; that’s separate. Basically, fulfillment centers are warehouses that break down and pack goods into boxes for delivery, which could ultimately be several states away: sorting or “sortation” centers get the boxes onto trucks, and their destinations are usually local. Some facilities do both; at Pinnacle Park, they’ll be separate operations. Delivery stations are different still: they get stuff onto cars and vans for last-mile delivery.

None of this is glamorous work; people get hurt, and there’s tremendous pressure to pack and sort goods quickly and continuously for an entire shift. These are the Amazon workers most likely to protest working conditions, go on strike, catch COVID-19, and get surveilled and sometimes retaliated against for labor organizing, both in the US and worldwide. In September, Detroit congresswomen Rashida Tlaib and Debbie Dingell toured a local distribution center in Romulus and found what they called unsafe working conditions. But Amazon is very concerned about the public perception of these warehouses, offering tours to journalists and politicians, and championing the fact that the company’s employing so many people.

(There are announcements for new warehouse centers All. The. Time. Amazon’s shipping capabilities are growing incredibly fast.)

It’s difficult but (at a minimum rate of $15 an hour) fairly well-compensated blue-collar work. It’s a lot more like a job at UPS than one at Microsoft or Google, and it’s the Microsoft/Google-type jobs that Amazon prefers to keep in Seattle, New York, and northern Virginia. Despite the presence of the nearby University of Michigan and Lawrence Tech, the strong presence of Intuit, and the city’s strong desire to reinvent itself as a high-tech hub attractive to white-collar workers, that was always a longshot.

But there are a lot of people in metro Detroit looking for jobs like these. And because so many Amazon customers live nearby, whether in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, or Ontario, there’s a huge demand for the services they offer.

The new casino

Anyways: it turns out Wayne County doesn’t actually own the Pinnacle Park site any more. Can you imagine? Just when they found such a promising tenant! The county sold it in mid-December, not even a month ago, to two developers, Hillwood Enterprise and the Sterling Group, who paid $4.9 million after the county spent more than $35 million in the mid-00s adding roads and water and sewer lines. Hillwood and Sterling, in turn, are going to develop the site for Amazon. The county even sold them an extra 350 acres of land (the racetrack complex is just 300 acres) just to help get the debt and its interest off their books.

“We inherited a bad situation with the Pinnacle Race Track. In light of that history, we quickly engaged the local communities to find the best solution for the property following its April 1, 2019 foreclosure," said Assistant Wayne County Executive Khalil Rahal. "We knew we needed a usage that fit better in with the assets around it and economic trends regarding logistics and distribution. We’ve done that.”

Rahal said the site is a good one for mixed-use industrial development.

"The fact that Hillwood was willing to move forward with these buildings before securing tenants tells us they expect the property to be in demand and that’s a great sign,” he said.

The thing is, Rahal didn’t really need to play coy here. Hillwood specializes in developing properties for use by Amazon, and the Sterling Group, a local development firm run by the well-connected Torgow family and long based in downtown Detroit, worked with Hillwood on the deal for Amazon to build a fulfillment center in Shelby Township, MI last year. Both companies are also in charge of the State Fairgrounds and Silverdome sites. It should have been no mystery that they were buying the properties for use by Amazon; the news just came when very few people (myself included) were paying attention.

If I sound a little testy about all of this, I am. I was born in Detroit, and have lived in or near it most of my life. Detroit has some troubling history, as most people know. And one of the particularly troubling things here, like in so many other cities, is that often local officials seem to be working on the behalf of powerful developers more than the citizens they represent and have sworn to serve.

Most of Detroit’s citizens have been suffering for a long time. But for developers, this is boom time. Detroit’s downtown, at least until COVID-19 hit, was coming back. People with wealth were spending it in the city. There are new sports stadiums, restaurants, hotels, and loft apartments downtown. For a minute, it even looked like Detroit might become the site of Amazon’s HQ2. The city even offered Amazon $4 billion (with a B) in tax breaks and other incentives if they’d come to Detroit, helping to drive up the price for New York City and metro Washington, D.C., who secured the bid. You can make a lot of money off a poor city that’s desperate to not be so poor any more.

There is not much that happens (or doesn’t happen) in the city of Detroit, or in Wayne or Oakland or Macomb counties, without the right people getting paid or otherwise benefitting from it. Amazon is building new facilities in metro Detroit because someone is benefitting from it, and it’s not just or even primarily Amazon or the people of Detroit who are doing so. And after the entire history of this city, I can’t trust local officials to do the right thing for the good of the people. Not when there’s much money involved, or a chance to announce so many jobs created and tax revenues gained, and so much political clout to be gained, transferred, or wielded.

Nor can I trust that those projected jobs and tax revenues will ever materialize. If you want to know why, let’s just look at what happened with the racetrack in Pinnacle Park.

Here is the backstory

In 2007, Jerry Campbell, the founder of Republic Bank and an avid horseman, announced plans to build Pinnacle Park Race Course, a thoroughbred track on the property, the first such track in metro Detroit since Ladbrook Detroit Race Course in Livonia closed a decade earlier.

Wayne County officials quickly jumped on board. In early 2008, the county issued $19 million in bonds to build roads on the property and another $14 million to install sewer lines.

The project's critics immediately raised doubts about its viability, given the failure of DRC, the decline of the industry overall and fact that Michigan didn't allow the placement of slot machines at the track to make it a so-called racino…

The county agreed to sell 320 acres property to Campbell for $1 with the understanding he would create 1,200 jobs there in five years. If the jobs failed to materialize, Campbell was to pay the county $16 million, or $50,000 an acre.

The deal also called for Pinnacle's owners to pay Huron Township $700,000 a year to help defray the costs of the road and sewer bonds.

The track opened in July 2008. Two months later, an economic meltdown started the recession and the foreclosure crisis.

In 2010, the racetrack closed. Campbell never paid the promised $16 million, the $700,000 a year, or even his $2.5 million tax bill. The county spent a fortune for bad guarantees and a foolish belief it could make more than its money back. That money was used to turn the site into a perfect racetrack — or, eventually, a perfect light industrial center — but created so many recurring costs that they had to sell it on the cheap just to get it off its books, with the hope that someone, anyone, might be able to turn it into a revenue-producing property again.

And who’s that someone? It’s Amazon. Is the county going to make its money back? No. Not even the rosiest projections for jobs and new tax revenue promise that. All of the profits are going to go to Amazon and its developer partners. All the money announced in today’s press release about job retraining for Detroiters, investment in STEM programs in local schools, and so on, is certainly welcome, but it’s pennies against dollars in terms of what has already been paid.

And no, Amazon is not getting tax incentives or other bonuses. It doesn’t need them. It’s getting a perfect location right by a major airport that will help it distribute its packages all over the region, and it’s getting that location at an incredible bargain. And this is what Amazon and other companies of its size. power, and popular appeal are able to do over and over again in cities and towns across the country.

Now, to put my cards completely on the table: my father worked for Wayne County for more than 40 years, first at the jail, and then for the county executive, including when his longtime boss, Robert Ficano, was convinced to invest the county’s money in this racetrack. My father and other people in the county argued that the money could be better spent securing the pensions and health care plans of the county’s many retirees, which they could have done at that point for a fraction of their future costs. But that wouldn’t have provided the lure of extra money, a chance to point to new buildings built and jobs created, and big, swanky events where Ficano (who’d eventually get invested by the FBI for corruption not long after my father retired and lose his office in disgrace) could show everybody what a big deal he is, just like Detroit mayor Mike Duggan is doing now.

So, yeah. My parents would lose their health care plan before they qualified for Medicare, all because of this stupid idea for a racetrack/casino in an out-of-the-way exurb nobody went to unless they were going to the airport, the site of which is now being developed by Amazon (the company I cover) so they can ship packages faster to my house. I am… unusually invested in this one. Life can be funny that way.

What’s Fair is Fair

Now, the Pinnacle Park site will probably play an important role in moving cargo, but the biggest Amazon distribution site in metro Detroit is going to be at the former State Fairgrounds. And the Detroit Fairgrounds site, and Amazon’s involvement with it, is also very controversial.

I saw my first concert here (if you don’t count Sesame Street Live) in 1997, when I was a newly-minted college freshman; The Verve Pipe (whose big hit was “Freshmen”) were playing a free show right where Amazon’s new robotics fulfillment center is going to be.

As you might guess, at that time, this was the site of Michigan’s annual State Fair until a few years ago, when it too moved out to the western suburbs. Over a century ago, people used to race horses here too. And in the 1990s, before The Verve Pipe even, there was a push to bring horseracing back to the State Fair before it was met by fierce community opposition, culminating in a quashed 2000 proposal for a mixed-development site including a racetrack. (I don’t know why, but this story has a lot of horses. Maybe it’s a metaphor for things that symbolize power, speed, and economy but are inevitably transformed if not outright displaced by time.)

The Great Recession ended the State Fair at the Detroit Fairgrounds site in 2009, when the state government stopped funding it. It picked up again in 2013, but in Novi, northwest of the city proper. The state of Michigan and city of Detroit have been in a long war with each other, and the state simply did not want to continue to fund a site owned by the city. Even without the State Fair, upkeep of the site cost over a million dollars a year.

So for a long time, the site malingered. In 2012, neighbors and community advocates, including Karen and Frank Hammer from Detroit’s Green Acres neighborhood, founded the State Fairgrounds Development Commission. The next year, a plan was hatched for a group led by Lansing-born Earvin “Magic” Johnson to develop the site. No horse racing or casinos this time:

The plan was pitched as the fairgrounds’ best shot at a second chance: A $120 million mixed-use development covering 500,000-square feet and featuring plans for retail outlets, residential development, parks, a cineplex, a “big-box” retail anchor, and a senior living home. The plan sought to renovate historic buildings and revitalize the fairgrounds into something that looked more like an outdoor mall.

For the Hammers, however, a plan to shuffle the fairgrounds to a private developer was riddled with concerns about a lack of public involvement. That year, the State Fairgrounds Development Coalition rolled out its own ambitious proposal, a “21st century sustainable concept” dubbed “META Expo.” The acronym, derived from “Michigan Energy Technology Agriculture,” was based on a wish-list of items gathered from the coalition’s community outreach. The concept would transform the fairgrounds into a regional transit hub, complete with solar arrays, greenways, a “geo pond,” and even plans for further urban development to the south in Penrose.

“People coalesced around trying to find use for the land,” Karen Hammer says. “The whole idea was that this would be a 21st century development that would encompass climate, sustainability, and reducing Detroit’s carbon footprint.”

Those ideas inspired the community advocates, but they didn’t find purchase in the places where it mattered.

Magic Plus LLC is still going to develop a small portion of the site, and there is still going to be a new transit hub, somewhat awkwardly placed away from the main corridor on Woodward Avenue. But the bulk of the site will soon belong to Amazon.

This is where we run into trouble. In 2018, the city of Detroit bought 142 acres of the Fairgrounds from the state for $7 million; Magic Plus bought the remaining 18 acres for an undisclosed price. For most of 2020, the Fairgrounds were Detroit’s primary site for free COVID-19 testing.

In August, Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan announced that it would be selling the Fairgrounds to a private development group, led by Hillwood and the Sterling Group, with the goal that it would become an Amazon distribution center. The historical buildings would be knocked down, and the community would have no real input on what was built on the site. The developers would pay $7 million for the transit hub, but (it eventually was revealed), that $7 million would be counted towards their purchase price for the site. Detroit’s city council approved these terms.

All told, Amazon and its partners would pay $16 million to the city of Detroit: $9 million for the site and $7 million for the transit hub. Again, pennies to dollars when you consider both the real value of that land and the $400 million total cost of the site when all the money’s been poured in. The city was able to write off the ongoing cost of the Fairgrounds and technically bank a small profit. But it was foregoing any control over how the site would be used, and the vast majority of profits from its future development.

In October, the SFDC sued to stop the sale, on the grounds that the city did not allow for community input before selling and rezoning the Fairgrounds, and that the site was sold for many millions of dollars less than it was worth. A circuit court judge issued a temporary injunction to stop the sale, but this decision was reversed by a Michigan appeals court… on November 3, Election Day. That day and in the days that followed, virtually nobody was paying attention, even in Detroit.

Amazon and its partners were free to go ahead with their big Detroit push, but they needed one more piece. They needed that land near the airport at the Pinnacle Park site. Once they’d secured that, they could make their big announcement.

Who’s to blame?

I should be clear about this: I don’t have evidence that Amazon’s technically done anything wrong here. The company and its employees have pushed for the best deal they could get, using all of the levers available to them. They’re not necessarily the bad guys, except insofar as they’re always the bad guys — that any company of its size, power, and popular appeal would end up being the bad guys to somebody in this situation.

My issue is overwhelmingly with local officials—city, county, and state—who have not proven themselves capable of objectivity, sound judgment, or even simple honesty when this much money is floating around or this much political hay to be made. Mike Duggan and Warren Evans will get to point to all the jobs Amazon will create, a transit hub they didn’t have to pay for, and a projected $42 million net benefit to Detroit over a 10-year period just at the Fairgrounds — and their counterparts in Oakland and Macomb counties will be able to do the same for the sites in Pontiac and Shelby Township.

Just as with HQ2 in Queens, politicians and other local officials are so enchanted by the possibilities of big-time real estate development that they’re willing to forego the hard work of actually making sure that development benefits the people in those communities beyond the sole possibility of a job that might save your life, but also might crush you to death.

In this respect, Amazon and gentrification of Detroit’s commercial corridors is just another horsetrack, just another casino. Amazon’s business prospects are a lot better than those of the people who dreamed of lifting up the city through gambling, but the gains are just as privatized, the losses just as shared. The right people got paid; the rest of us might get screwed.

Where is all this headed?

There’s one more shoe to drop here. Hillwood and the Sterling Group have already taken on the State Fairgrounds, the Pontiac Silverdome, and the Pinnacle Park racetrack. The Sterling Group has also petitioned to buy and develop the former site of Joe Louis Arena, another former sports and entertainment venue downtown, as well as a nearby parking lot. Nobody knows (or at least, nobody is telling) what they want to do with the site.

It might not be for Amazon. The Sterling Group owns a lot of properties downtown. Lots of wealthy people, families, and companies own huge chunks of Detroit. Billionaire Dan Gilbert, founder of Intuit and owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers, has a ton of development projects in the city (which is one reason he led the effort for Amazon to bring HQ2 to Detroit). The Ilitch family, who own the Detroit Tigers and Red Wings, bought up and intentionally blighted most of Woodward Avenue so they could buy up even more of it as cheaply as possible before getting a huge gift from the city to build a new sports stadium, Little Caesar’s Arena, conveniently located near the commercial properties it already owned. There are a ton of ways to make money off Detroit real estate that don’t involve Amazon at all.

All of them, for decades, have been waiting to flip the switch, for Detroit to turn from economic no-man’s-land to a place of unlimited economic opportunity. They want to get rich. But they all also want to get credit for saving the city whose dire state (real and perceived) they worked to create. And some of them quite openly wish that Detroit’s current residents were replaced by different people: better people, smarter people, whiter people. Above all, people who will buy what they have to sell and increase the value of what they already have. As if Detroit’s problems all along have been the people, and not the conditions people with wealth and power have constantly done their best to create.

And that makes me go white-hot with rage.

Even Joe Louis Arena was sold for a song. First, it was given away to one of Detroit’s creditors when the city went bankrupt. (That bankruptcy, too, wasn’t caused by declining population and revenue so much as an extremely risky — I’ll say it, totally crooked — debt financing scheme that completely fell apart when the city’s bond rating was downgraded. It was led by a Republican-governor-appointed city manager, and its intention was to ruin Detroit and enrich well-connected people, just as that was the intention when the state-appointed manager of Flint disastrously decided to switch that city’s water source.) Then, when people with competing interests made developing the site difficult, that creditor moved to sell the site to the Sterling Group.

Pennies to dollars. Some people get pennies; other people get dollars. Amazon makes dollars every time it saves pennies. In this situation, the company’s neither good, nor bad — okay, the working conditions in the warehouses are pretty bad — but neither are they neutral. Just like technology itself, they warp the gravitational field of everything they touch. And we are, all of us — cities, states, companies, and nations — caught in its well.