Tolkien and Amazon’s Fight for a Franchise

The Lord of the Rings prequel is a play for prestige, popularity, and return customers

Amazon is spending a huge amount of money on its new multi-season television series set in J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy universe: an estimated 250 million USD for the rights and 465 million USD just for the first season, making it quite likely the most expensive television series in history. This raises the question: just what is Amazon buying with all that money, or rather, what does it expect in return?

If the new Lord of the Rings-verse series is a tentpole, it’s a tentpole of a different kind: it’s not necessarily driving subscription numbers like an HBO series, and it’s certainly not anchoring an evening of programming like a network TV series. In 2019, Amazon Studios head Jennifer Salke outlined Amazon’s strategy this way:

We have a very unique business in the sense that our entire north star is to entertain and delight Prime customers all over the world, so there’s a different strategy there… We will curate shows to bring to that global, diverse audience. We’re not in the volume business. We’re in the curated business… I came from the network business, as did all of us, where you’re used to being able to go out and talk about success in viewership numbers. Our company doesn’t embrace that strategy.

In other words, Amazon is looking for a halo effect: a boost in subscriptions and sales, sure, but also buzz, awards, a reputation in and around Hollywood and worldwide that Amazon is a good partner and a good place to do business. It’s the same thing as always, but more.

It’s also looking, as much as possible, for tie-ins across the Amazon line — and in this sense, the Tolkien universe is uniquely well-suited. While the Hobbit films are for the most part not greatly admired, they did good business despite an awkward production, and the Lord of the Rings series has won major awards and been an icon for two decades. And the books’ reach remains deep, not just the single Hobbit book and the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but the headier stuff of the First and Second Ages from the appendices, The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and the History of Middle-Earth, which the new series is (partially) opening up for nearly the first time.

Nearly all of these books are available for Amazon Prime readers on Kindle Unlimited. It’s quite possible that no movie or television series in history comes with so much reading material via a single subscription.

However, this is where the rights situation gets a little awkward. If you’re unfamiliar with the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, a quick summary might be useful.

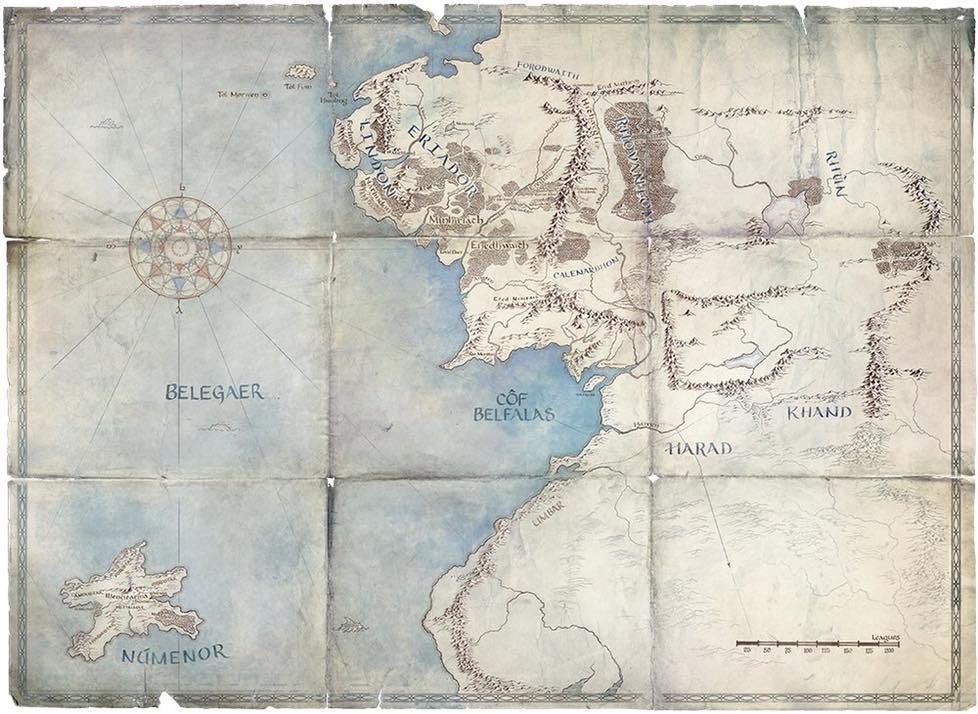

In his lifetime, J.R.R. Tolkien published two works of fantasy set in a section of the planet Arda called Middle-Earth: The Hobbit and then its multi-volume sequel The Lord of the Rings. While there are hints of other lands and ages in The Hobbit, it’s really in The Lord of the Rings that it’s decisively revealed that these stories take place at the end of the Third Age of Arda, and there are other parts of that world, most now lost, including Beleriand, Númenor, and the heavenly Valinor, among others.

The characters Aragorn, Boromir, and Faramir are descendants of the Númenoreans, wise and long-lived human beings whose Atlantis-like island continent was destroyed by the gods in the Second Age of Arda when they dared to sail to (and make war on) Valinor. The new Amazon series is about those Númenoreans, who traveled all over the world during the Second Age while under a ban never to sail west to the land of the gods. They (and in some cases their descendants, or their slaves) are responsible for much of the legendary architecture encountered in The Lord of the Rings. (If it wasn’t built by elves or dwarves, it was the Númenoreans.)

Over his life, J.R.R. Tolkien wrote and revised many stories about the First Age. These were collected and edited after his death by his son Christopher, and published in the books The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, Beren and Luthien, The Children of Húrin, The Fall of Gondolin, and others. It’s a rich and full mythology, and a television studio could take years to tell those stories.

Amazon has the rights to none of them. The Tolkien estate didn’t sell those. (And Amazon doesn’t have the Hobbit/Lord of the Rings-era stories either.)

What the Tolkien estate sold was the rights to the Second Age, but reportedly not the parts of those stories told in the books primarily about the First Age (the Silmarillion, etc.) At the same time, Amazon cannot contradict those stories either. Amazon’s series will have to be consistent with the Tolkien canon, while at the same time drawing on the vaguest, least detailed portion of it: genealogies, a few outlines of stories, and not much more.

On the one hand, this gives Amazon a remarkable degree of freedom in creating and new characters and defining ones only briefly sketched. And it also allows for a degree of suspense that would be absent from a retelling of the stories of the First or Third Age; while we might know the whole thing ends in catastrophe, we know much, much less about how we arrive there.

Tolkien biographer Tom Shippey (who at one point was involved with Amazon’s production) puts it this way:

Amazon has a relatively free hand when it comes to adding something, since, as I said, very few details are known about this time span. The Tolkien Estate will insist that the main shape of the Second Age is not altered. Sauron invades Eriador, is forced back by a Númenorean expedition, is returns to Númenor. There he corrupts the Númenoreans and seduces them to break the ban of the Valar. All this, the course of history, must remain the same. But you can add new characters and ask a lot of questions, like: What has Sauron done in the meantime? Where was he after Morgoth was defeated? Theoretically, Amazon can answer these questions by inventing the answers, since Tolkien did not describe it. But it must not contradict anything which Tolkien did say. That’s what Amazon has to watch out for. It must be canonical, it is impossible to change the boundaries which Tolkien has created, it is necessary to remain “tolkienian”…

The First and Third Ages are “off-limits”, you can’t have the First Age. Events could be mentioned at the most if they explain the events of the Second Age. But if it is not described or mentioned in the Lord of the Rings or in the appendices, they probably cannot use it. So the question is to what extent they may hint at events that took place, for example, in the First Age, but still continue to affect the Second Age. There are several maps authorized by Tolkien, not just the ones we’re are familiar with, and some of those maps have places on them which are not in the other maps. But if Tolkien authorized them then that’s okay. So it’s it’s a bit of a minefield. You have to tread very carefully but at the same time there is quite a lot of scope for interpretation and free invention.

So Amazon on the one hand has this rich tapestry of texts for viewers to call on in order to understand the television show; but on the other, there’s very little in the texts that will give them a definitive answer one way or the other.

Here’s an example of the kinds of reading that we’re likely to see. Look at the promotional image Amazon Studios has offered again, reportedly from the first episode. There’s an ancient city and a tree with a bright light. But which city and which tree is it? Here’s a relevant section from Akallabêth, the short history of Númenor from The Silmarillion:

Of old the chief city and haven of Númenor was in the midst of its western coasts, and it was called Andúnië because it faced the sunset. But in the midst of the land was a mountain tall and steep, and it was named the Meneltarma, the Pillar of Heaven, and upon it was a high place that was hallowed to Eru Ilúvatar, and it was open and unroofed, and no other temple or fane was there in the land of the Númenóreans. At the feet of the mountain were built the tombs of the Kings, and hard by upon a hill was Armenelos, fairest of cities, and there stood the tower and the citadel that was raised by Elros son of Eärendil, whom the Valar appointed to be the first King of the Dúnedain…

But the wise among them knew that this distant land [to the west] was not indeed the Blessed Realm of Valinor, but was Avallónë, the haven of the Eldar upon Eressëa, easternmost of the Undying Lands. And thence at times the Firstborn still would come sailing to Númenor in oarless boats, as white birds flying from the sunset. And they brought to Númenor many gifts: birds of song, and fragrant flowers, and herbs of great virtue. And a seedling they brought of Celeborn, the White Tree that grew in the midst of Eressëa; and that was in its turn a seedling of Galathilion the Tree of Túna, the image of Telperion that Yavanna gave to the Eldar in the Blessed Realm. And the tree grew and blossomed in the courts of the King in Armenelos; Nimloth it was named, and flowered in the evening, and the shadows of night it filled with its fragrance.

So which f—ing tree is it? It’s probably not Telperion, the original white tree, the one Morgoth destroyed, because there were two of them. But it could be any of these seedlings, from Galathilion on down to Nimloth. My money’s on Nimloth. But do we know? We don’t really know, and aren’t going to until (maybe) the show airs.

So we have the opportunity for a lot of fan service, a lot of hints and nods and winks to stuff from the First and Third Ages that fans of the books will enjoy. But very little of it might be resolved decisively in terms outside of the show itself.

This seems like a tricky dance, and it’s hard to say exactly what sort of pleasure fans will derive from it. After all, millions of people who greedily watched The Lord of the Rings in movie theaters (remember movie theaters?) and then bought the movies in special extended editions on DVDs (remember extended editions and DVDs?) knew more or less exactly what was going to happen in the stories. They were watching to see how those stories would be brought to life, to have familiar tales told to them again, in a new way.

If Amazon is going to pull this off, it has to hope that both hard-core and Tolkien fans will be equally devoted to what the studio is offering, either because of the nature of the source material or the quality of the storytelling, and equally eager to learn more. This is, after all, the difference between a series and a franchise: a franchise gives you room to return to it again and again, from a thousand and one angles, over space, media, and time.