A small news story slid in over the weekend, but I think it’s noteworthy enough to take a second look. It’s an interview with Bookshop.org’s Andy Hunter by Techcrunch’s Danny Crichton. There’s a lot of data here. For example:

Bookshop’s sales are in 2021 are about even with where they were in the site’s annus mirabilis of 2020, when the site took off as physical bookstore sales dipped. This year, bookstore sales are largely back, but Bookshop’s sales remain strong.

Bookshop is working (and helping its partner stores) to invest in human-curated book recommendations, rather than wrapping both arms around an algorithmic model. This could be a good differentiator going forward, both for Bookshop and between different bookstore partners.

This ia also (we hope, and Hunter hopes) good for midlist books and ones by less established authors, which often get crowded out by blockbuster-driven algorithms and media hype.

All this is good. But here’s one item in particular that I wish had gotten more attention:

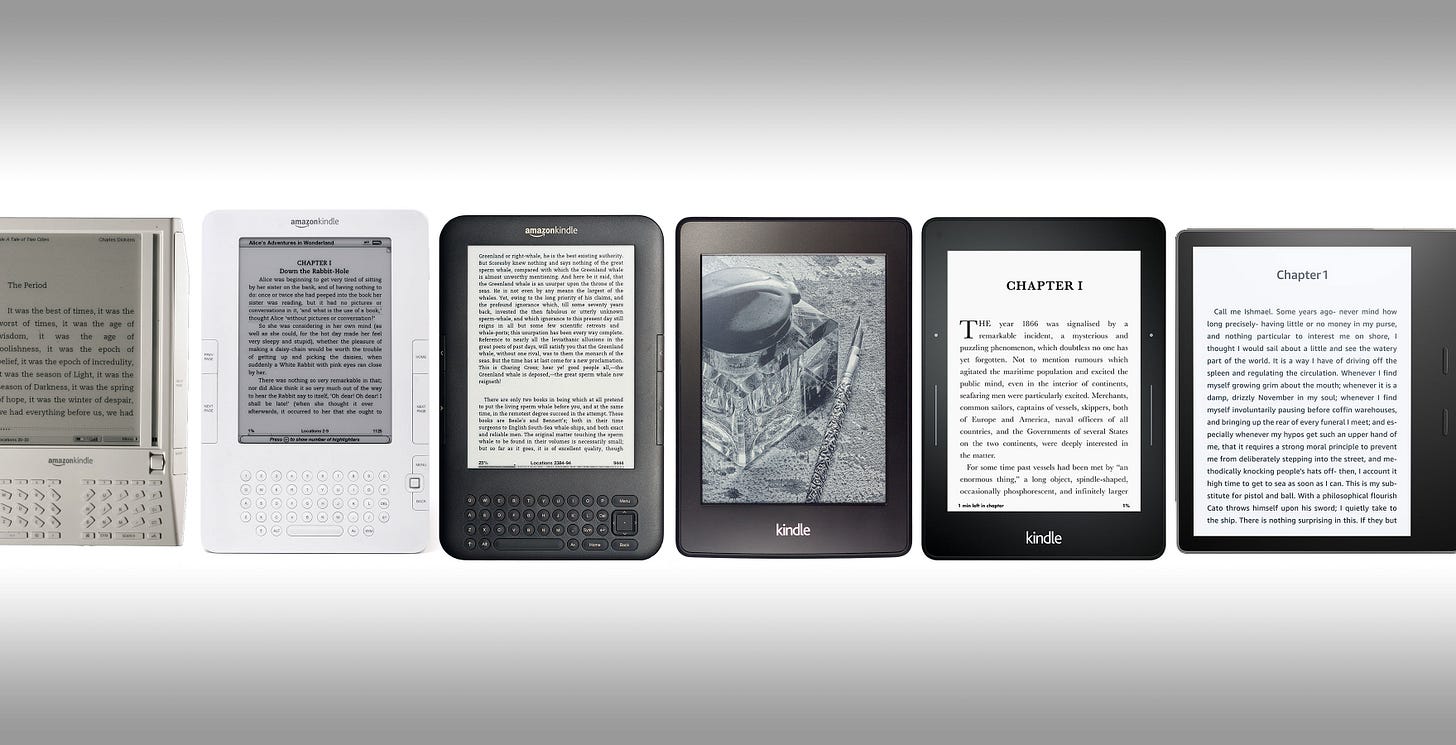

Amazon, of course, is the biggest challenge for the company. Hunter noted that the company’s Kindle devices are extremely popular, and that gives the e-commerce giant an even stronger lock-in that it can’t attain with physical sales. “Because of DRM and publisher agreements, it’s really hard to sell an e-book and allow someone to read it on Kindle,” he said, likening the nexus to Microsoft bundling Internet Explorer on Windows. “There is going to have to be a court case.” It’s true that people love their Kindles, but even “if you love Amazon … then you have to acknowledge that it is not healthy.”

There is a lot going on here! Let me try to spell it out.

Essentially, Amazon has the most popular e-readers and the most popular e-bookstore. These are not unrelated. While Amazon’s e-books do work on other companies’ devices (phones, tablets, laptops), they won’t work on other companies’ e-readers, nor will e-books from most other digital bookstores work on Amazon’s e-reader, and in both case, it’s for the same reason: DRM. Amazon DRM won’t work outside an Amazon device or application, and Amazon won’t let books with other companies’ DRM work on the Kindle.

So Bookshop (which doesn’t sell e-books, but perhaps someday could) or any other company with a digital bookstore can’t get their books on the Kindle as long as they’re packing DRM. And this isn’t just limited to Barnes & Noble or Kobo or Apple or other companies selling e-books: it means libraries have to make special accomodations for Kindles, digital subscription or streaming services have to target phones or tablets rather than Kindles. (On top of that, Amazon also uses slightly different formats for its e-book files rather than the EPUB standard, which makes it technically incompatible in another obnoxious way.)

For this reason, the e-book and e-reader marketplaces are very different from, say, smartphones or TV set-top boxes. While there are some incompatibilities and unavailabilities that drift towards ecosystem lock-in, for the most part, buying a device gets you access to a wide range of popular content options. E-readers are different. When you buy a device, you’re buying a bookstore, and vice versa.

There is — or at least, could be — an alternative. If e-readers and e-bookstores were not so tightly coupled, and a certain amount of intercompatibility were guaranteed, then someone with any e-reader could buy books from any e-bookstore, borrow them from any library, or subscribe to them from any service on their own machine.

Admittedly, that would still limit the field to companies who can afford maintaining the expensive overhead for DRM. If you eliminated DRM as a factor altogether, then any publisher that chose to be could also be a digital bookstore; every print bookstore could be a digital bookstore. Indeed, you or I could open digital bookstores and sell e-books at a small markup, competing on the best curation, the best recommendations, or the best additional services we could offer to justify our margins. (Piracy would almost certainly be a problem for these booksellers, but it could, in principle, be done. At this point, most of my digital book purchases comes from publishers who sell their books without any form of DRM.)

Part of the trouble is that the additional services offered by e-bookstores is so closely tied to DRM. Now, it is easy to point to DRM or to Amazon or to the major publishers who insist upon things being done a certain way as the villains, and I am not above doing that. But it is difficult to see how Amazon, for example, could sync a customer’s current pages read across devices on applications where it cannot exercise some sort of digital control over the app or object being read. That’s one of the benefits you lose without cross-platform DRM.

To a certain extent, though, this entire discussion is moot. Amazon has largely won the marketplace; alternatives exist, and customers are free to choose them, but Amazon certainly has no incentives to change how it makes its e-books available or to further open up its own machines. True! But perhaps a court of law might decide that such arrangements were anticompetitive and could change, whether prodded by a competitor (like Bookshop) or by the Department of Justice (which is taking a much different view of what is and isn’t anticompetitive behavior than it has in other administrations).

This is why Hunter’s admission that “there’s going to have to be a court case” is tremendously interesting, and suggests that the world of e-books, e-bookstores, and e-readers, placid as it’s been since the introduction of the touchscreen more than a decade ago, could very quickly get a lot more exciting.

I’m going to do something a little unusual for me and open this up for comments from subscribers. What would you like e-books and e-bookstores to look like? What changes would make them better? And which changes are more likely or unlikely to happen because of different stakeholders’ interests in the outcomes?

You can either comment below or reply to this email if you’d rather keep our correspondence private (although if you say something really interesting, I may ask for permission to quote you later on).