What’s the Point of a High-Tech Custom-Made T-Shirt?

Amazon Basics, but make it fashion

A lot of stuff happened this week. However, for the purposes of this newsletter, we’re going to confine ourselves to stuff that happened involving Amazon this week. Trust me: there’s a lot!

Most of it happened on Monday. The smallest one in the news cycle (but maybe the most important) was the one I chose to write about: Amazon’s continued construction of new sorting and fulfillment centers all over the world, including my hometown of Detroit.

Later, Amazon Web Services announced that it was suspending Parler’s account for violation of AWS’s acceptable use policy. Parler, having already been removed from Apple’s and Google’s app stores, had to shut down, and responded by suing Amazon. Amazon’s response to Parler’s motion for an injunction is 100% worth reading (although the threats of violence / bigoted slurs it shares from Parler’s forums are 100% disturbing).

Amazon also announced it was removing QAnon products from its retail platform, again in response to last week’s violent attack on the Capitol building and its environs by right-wing groups, resulting in several deaths and the disruption of the U.S. government.

And just last night (January 14th), the law firm Hagens Berman, who helped begin the lawsuit that resulted in a federal collusion charge against Apple and the Big Five book publishers ten years ago, filed suit in the Southern District of New York against Amazon charging them with conspiring with the same publishers to fix prices in the e-book market.

Am I going to write about these things? Do I have a long history with these topics and plenty more to say about them? Have I already done reporting that will help you see these events with (I hope) a new perspective? Of course.

Eventually.

In this newsletter, I have a different story about Amazon to tell you, one that I hope you’ll find just as important as those pressing events. It’s about t-shirts.

T-Shirts?

T-Shirts!

Amazon is selling made-to-measure custom t-shirts for $25 apiece. But because it’s Amazon, it’s not doing it in the usual way. Amazon doesn’t take your sizes or even your measurements. You can’t even give that information over if you wanted to. Instead, Amazon asks for your height and weight, and then has you use its smartphone app to take pictures of your body (one standing straight up with arms out and one in profile) so it can use cloud-based science to calculate what the size and shape of your t-shirt ought to be. It’s pretty weird.

After you’ve taken and submitted your photos (which is not trivial: you need a reasonable amount of space and a wall or door to prop up your phone at the proper angle; then, you position your body as the app commands, and it takes the picture), you can customize the shirt further, picking the material: either 100% cotton or a lighter, stretchier, blend of cotton, modal, and elastane. You can also choose the color, long or short sleeves, a longer or shorter cut, V-neck or crew neck, and if you choose, a custom label.

I was nervous taking these pictures and making these choices. To be honest, I wasn’t thrilled about giving the Amazon app access to my camera. (The images may be deleted after your 3D avatar is created, but the app permissions sure aren’t.) I shop at Big and Tall stores. I can’t buy most retail clothes. I wanted some assurance that the company would even make a shirt in my size before I gave them all of my data. I received nothing of the sort.

But — luckily, I guess? — Amazon was willing to make a shirt that fits me after all, and at the promised price. (I have no idea what the limits might be, or if they even exist.)

I ordered the T-shirt ten days ago, on January 5th. According to Amazon, a shirt typically takes five days to manufacture. UPS took control of the package on January 11th in Gardena, CA, and it arrived in Detroit today, January 15th.

I just put it on, before hitting send on this email. It fits! The lightweight blend is very soft and stretchy, but a tad sheer for my taste. (I probably would have been happier with the medium-weight cotton.) The collar is a little high but not uncomfortable. The short sleeves are, well, a little short. It’s… fine.

Ten days is not such an unusually long time to wait for an item of custom-made clothing, but it is an unusually long shipping time for an item from Amazon. I am curious about the shipping because I am curious about where and how the t-shirt was made. Was it made in or near Gardena, a Los Angeles suburb with a large Korean- and Japanese-American population and a history of low-paid industrial and agricultural work? Was it made in another country and shipped across the Pacific Ocean (or, somewhat less likely, the Mexican border) into Gardena?

(One mystery almost solved, but sadly, after publishing: the tag on my shirt says “Made in the U.S.A. with imported fabrics.” OK! But are the people who made it Amazon employees? Are they subcontractors? Are they eligible for Amazon’s $15/hour minimum wage guarantee? Are they paid better than that? Where do the fabrics come from? I would like to know more!)

There are questions that are not answered by Made for You’s helpful FAQ. In fact, I couldn’t find anyone who was even willing to speculate where and how these shirts were made, or how they could be sold at such a low cost. Even if Amazon isn’t doing hand tailoring and adjustments, it still has to reset a machine, or invest in a machine that can change sizing on the fly. All of that costs money.

(My go-to source on this used to be my older sister Kelly, who passed away in April. A big part of her job was working with apparel manufacturers in China, which is where most of your favorite companies make their goods. She could tell you what a change in material or a change of labor cost, down to the penny, and exactly why one bag or coat cost more or less than a different version that might look almost identical. As is, I’m a tech reporter, and like most tech reporters writing about one of the many industries Amazon touches, I’m working without a net. I’m writing all of this to let you know that I know that this is a clothing, manufacturing, and labor story as much as it is a fun excursion into e-retail or “geez, why does Amazon want more creepy photos of my body?” story. And that I’m doing my best to tell it as such, with the limited information I have.)

Still: the more I thought about it, the more it seemed strange that Amazon was offering its customers such a limited number of customization options. I couldn’t even request a tigher or more relaxed fit, or add a ringer collar or sleeves in a different color from the rest of the shirt — all pretty standard options for basic tees, let alone custom jobs. You can’t even put a pocket on the chest. Why only a custom tag and not a monogram?

Even the available colors are currently limited to only eight. Why just these eight? And why do I have to give you my height and weight and photographs before I can find out what the colors even are?

And why t-shirts? Why not sweatshirts, or polos, or leggings, or dresses, or socks? It seems bizarre to take photos of my entire body and animate a little 3-D avatar just to slap a monochrome t-shirt on it. And why is it only available to customers in the United States?

I wanted to know what else was out there, and why Amazon had made the choices it did. So I did what I’ve always done as a reporter: I asked the competition. Who are some of the other people who make made-to-measure clothes you can buy online? What do they do, and how is it different from what Amazon does? And what can how those companies do business tell us about this emerging space in the fashion and apparel sector that Amazon’s trying to claim for itself?

Who else is making custom t-shirts?

To be clear, most of the “custom t-shirt” industry is really just simple prints (and sometimes patches) over commodity tees. These are everywhere. If you use Instagram or Facebook, you’re probably seeing an ad for one right now. There’s nothing truly custom about these shirts—although, again, they do usually offer more options for colors, fabrics, and styles than Amazon currently does.

There’s also the world of tailored shirts, which has been around basically forever and is still pretty low-tech. Either you buy a standard size shirt and then have it fitted and altered for your body, or you have one pinned and sewn either directly to your body or using a detailed set of measurements, taken in person by a tailor. It’s pretty rare that you would do this for a t-shirt, but it can be done. It’s just going to be more or less a one-off. And at least part of it is going to be in person. It’s really a different business.

So you have to look for companies that are making individually fitted shirts (including t-shirts) at scale that you can buy online.

So far as I can tell, there isn’t a single other company who’s doing it the way Amazon is, using photographs and height and weight alone. In fact, that’s a really bizarre way to make an item of clothing. It doesn’t really tell you, without extra analysis and finagling, what a tailor wants to know in order to make a shirt.

(Note: after initial publication, a reader recommended I check out MTailor, who similarly uses a smartphone’s camera and a software algorithm to generate measurements — nine for the upper body, seven for the lower body — that it uses to make a wide range of apparel for men and women, from suit coats to blue jeans. MTailor actually uses a 360-degree video rather than a front-facing and profile photograph like Amazon does. Which actually makes a lot more sense. The key point for me is: you don’t gather all this data if all you want to make is a t-shirt.)

I was able to identify two companies who are making made-to-measure shirts in a slightly more traditional way: using measurements. Moreover, both companies were much more transparent than Amazon was about things I wanted to know, like:

what is the material the shirt is made from? where was it sourced? is it environmentally sustainable?

where is the shirt itself made, and by whom? are the workers treated well?

what else can you offer besides t-shirts?

The first is Citizen Wolf, in Sydney, Australia, and the second is Son of a Tailor, in Copenhagen, Denmark. Both have been around for a few years, and have already been well-reviewed in magazine articles and sites online. They’re a bit pricier than Amazon and offer more upscale options, but at least for now, they’re the competition.

Citizen Wolf: Algorithms, Not Images

Citizen Wolf’s bread and butter is t-shirts, but they offer a lot more options than Amazon’s Made For You does. For women, they offer four different kinds of tank tops and 11 variations on a t-shirt, four three-quarter-sleeve shirts, and eight long-sleeved shirts, including mock and turtleneck options. Men don’t get tank tops, but can get front pockets and also turtlenecks for their tees.

For fabrics, you can pick organic cotton in three different weights (it specifies the GSM, grams per square meter, but it’s fair enough to call them “light,” “heavy,” and “medium”), a blend of hemp and organic cotton, or merino wool. Each material comes in different colors and costs a different price, but a men’s pocket tee ranges between $69 for lightweight cotton and $129 for merino wool. If you like, you can order swatches in different materials and colors before you buy. (They are pretty clearly targeting a different market than Amazon’s.)

All the materials are ethically certified, part of the cost includes a 5x carbon offset, and the shirts are made in Citizen Wolf’s headquarters in Sydney, all of which is included in the cost. CW is also willing to cover free tailoring if the shirt doesn’t fit perfectly and will honor special fit requests, like “I’ve got long arms, please add a few cm to the sleeve” or “lose the pocket on this one.” (Another example on the website says, “I’m actually a golden retriever, can I get a hole for my tail?”)

What’s truly interesting about Citizen Wolf is that it doesn’t ask for your measurements, although you can offer them. Instead, it asks for your height, weight, date of birth, and for women, bra size. Its algorithm, which it calls “Magic Fit,” uses these to generate a chest, waist, hip, and length measurement, and it uses these dimensions to make your t-shirt.

Basically, Citizen Wolf is trying to do the same thing as Amazon: offer a more expansive range of sizing for t-shirts than the standard S-2XLT without having to go to a tailor for measurements. It just does it without asking for your photographs.

Son of a Tailor: A more traditional approach, with some mysteries

At the same time, $69 is a lot of money to spend on a lightweight cotton t-shirt I’m not already convinced I’m going to love. I can get the Polo Ralph Lauren Supreme Comfort tees (60% cotton, 40% modal) from my local Big and Tall that I already know fit and feel great for half of that. So I kept looking, and found Son of a Tailor.

Son of a Tailor also asks for a small set of datapoints to create a custom size: height, weight, age, and (somewhat unexpectedly) shoe size. (Very helpfully for Americans, it allows input in inches and pounds as well as centimeters and kilograms.) Like Amazon and Citizen Wolf, it will save your selected sizes and custom options for future orders.

On a basic cotton short-sleeved t-shirt, you can get four different kinds of necks (crew and V, in standard or single stitch), two kinds of sleeves (classic or folded) and an optional embroidered monogram in the corner (initials only). This shirt costs $64, but you can get a discount if you buy two, and a bigger one if you buy in bulk.

The comapny also offers wool and pique knits, long-sleeved shirts, polos and henleys, sweaters and other pullovers, some “special edition” limited runs, and other cloth goods like caps, beanies, scarves, gloves, and face masks. (Sadly for those of us with unusually large heads, faces, and hands, these are only available in one-size-fits-most.)

It is fair to say that Son of a Tailor caters to men’s and so-called unisex styles much more than either Citizen Wolf or Amazon’s Made For You.

I bought two shirts, a cotton t-shirt and one in wool with long sleeves. There’s a discount for buying more than one shirt, so all told, I spent $140 on the two: kind of a lot of money for me, since I’m used to swooping things up on clearance, but (I thought) not so much considering I was getting custom clothing in quality materials with my own monogram, and (I hoped) a pretty good story.

I then contacted Son of a Tailor hoping to ask them more questions about their company and processes, and what they thought about Amazon’s entry into the world of made-to-measure t-shirts. After agreeing to an interview, my press contact offered to comp me the price of one of the shirts as a review copy. I agreed, although I let them know there was no way their shirt would arrive in time for me to do a proper review as part of my story. They were fine with that.

Since the shirts’ patterns have been cut but haven’t yet shipped, I still actually don’t know which of the two shirts I’m not getting charged for: I’m assuming the cotton one.

Son of a Tailor’s CEO Jess Fleischer was only available via email (the time difference caused us trouble), and couldn’t answer everything I asked. In particular, he was not interested at all in talking about Amazon or what other companies might be doing, or the possible benefits and drawbacks of working with customers’ photographs — all of which is, I think, understandable, albeit disappointing for someone as terminally hungry for information as I am.

Here’s what Fleischer said when I asked about where he saw the future of the industry next year, in five years, and ten years:

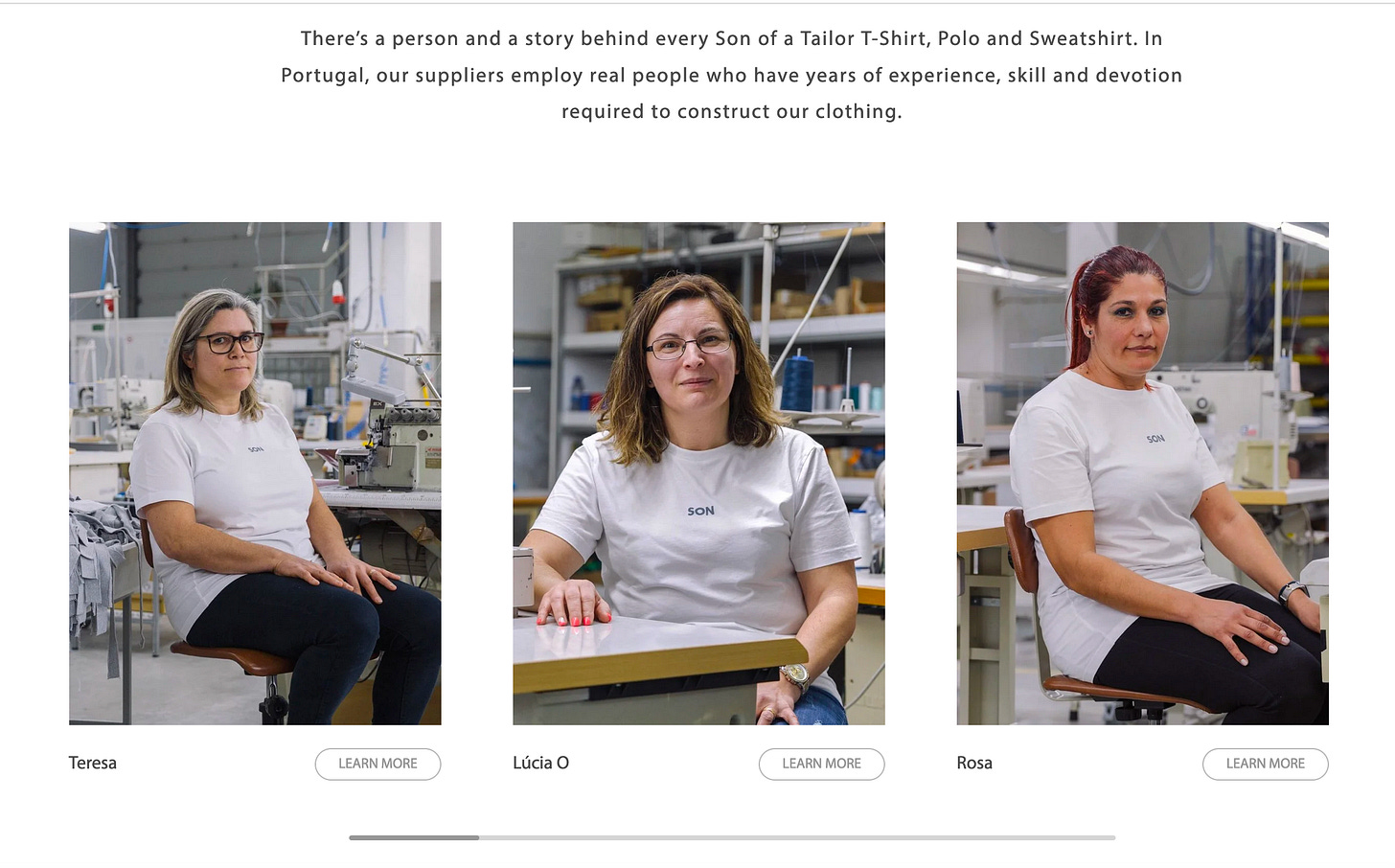

Son of a Tailor was born out of a frustration with the status quo of garment production. Clothes have been made, more or less, in the same way for decades, a way that is bad for the environment, the people who make the garments, and the people who wear them. Custom-made clothing has high potential in this regard as it eliminates overstock and drastically reduces waste while delivering a superior product to the customer. At the same time, this way of producing goes hand in hand with a very close relationship to the production partners which ensures good working conditions and transparency. At Son of a Tailor, for example, every piece of clothing comes with the name of the person who made it.

This is the big sell for Son of a Tailor (and really, for Citizen Wolf too): custom-made clothing isn’t an indulgence, but a necessity, because it’s less wasteful than commodity t-shirts that discard as much fabric as they use and wear out after a few years of light use. Custom clothing, these retailers argue, is better, fairer, and more sustainable.

That is… not really part of Amazon’s value proposition, at all. Nowhere in any of its promotional materials for Made for You does the company even attempt to make that case.

That is somewhat curious, given Amazon’s broader public commitment to environmental sustainability and the fact that a lot of Amazon’s customers are looking for a commitment to fair labor practices and sustainable manufacturing from the company and (so far) not finding it. Such a commitment, even in this limited case, might also reduce the sting of yet another case where Amazon wants to take pictures of your body — especially when, really, it could probably avoid doing so.

As well as putting the names of the tailors on each shirt, Son of a Tailor also highlights their suppliers’ employees on their website, all of them women who work in a factory in Portugal.

Now, one data point Son of a Tailor asks from its customers fascinated me, and fascinates me still. Date of birth, ok, that’s a little strange, but whatever. (I should probably actually be more curious about this.)

Son of a Tailor wants to know your shoe size. It does not sell shoes, or socks, or anything else that goes on your feet.

Full disclosure: I have very large, very wide feet. I also have enormous hands, a very large head, and extremely long arms. Like, total outlier, NFL-player big.

All of this makes buying shoes, socks, shirts, hats, and gloves very difficult for me. So I wanted to know: why does Son of a Tailor ask customers for their shoe size?

Here was Fleischer’s response:

All four inputs that we require from our customers when creating their custom size have proven to lead to improved results when it comes to the way the garment fits and, thus, to higher customer satisfaction. Height and weight are the most important inputs, followed by age and shoe size. Shoe size was initially not part of the mix but we realised that including it led to better results. In short, we only ask for inputs that we need to create the best fit possible.

I, of course (terminally greedy for information!), tried to find out more:

Can I ask one follow-up question? You can be as general as you want here: I don’t need trade secrets, it’s just an interesting detail that I appreciate and I think my readers will too. Broadly speaking: what kind of adjustments does a different shoe size indicate? Longer arms? A larger chest? (This may be different for men and women.)

It seems to me like a detail many on-site tailors might not notice or ask about — it’s certainly not something Amazon asks about or its images can capture — but it’s something customers know well, can relay to you accurately, and turns out to be relevant to your data and lead to better outcomes. I want to understand how, because that detail might help me explain how this whole process works. Does that make sense?

But alas, I was foiled:

I understand why this would be of interest but, unfortunately, we are not able to comment on that.

RATS!

Where is all this going?

Amazon is clearly not going to stop with t-shirts. It will also probably not go the high-minded, ethically-sourced, environmentally sustainable route Citizen Wolf and Son of a Tailor have taken. It’s going for inexpensive, influencer-driven casual basics and street fashion.

The Drop offers a good model here. The Drop is Amazon’s take on inexpensive, limited-edition, Instagram-friendly women’s basics.

That’s Amazon’s Made for You customer. If it can sell a few t-shirts to big guys with long arms and wide chests too, that’s gravy. Here is a survey Amazon gives to customers shopping its custom t-shirts:

Maybe they’ll expand the materials and options they offer on these clothes. Maybe we’ll find out more about where these items are made (and by whom) and how their materials are sourced. But for the moment, all you get is a $25 solid-color t-shirt with a pretty unusual shopping process. That’s not a bad price. But I’m not yet convinced it’s worth all the trouble.