Amazon's Game of Monopoly

Or, Different Countries, Different Rules

Welcome back to the Amazon Chronicles, your weekly update on all things Amazon. We have more than five hundred new readers this week! Thank you all for spreading the word. And a very special thank you to my 386 paying subscribers, who make the newsletter free for everybody. You are all champs. If you missed last week’s post breaking down Amazon’s quarterly earnings statement, you can find it here.

So wait, what’s happening in India?

One post I wish I’d included in last week’s roundup that, I swear, was in it until the very last moment when I feverishly was looking to cut space, is this note from Quartz India on Amazon’s and Walmart’s competition with Mukesh Ambani’s/Reliance’s new e-commerce portal.

Late last year, the Narendra Modi government announced several restrictive changes in its foreign direct investment (FDI) policy for online retailers, which was first floated in 2016. These changes could potentially force retailers to change their business models.

Among other things, starting Feb. 01, online marketplaces are barred from entering into exclusive deals for selling products on their platforms. Additionally, no more than 25% of the inventory on an e-commerce platform can be from a single vendor.

So far, online retail in India has grown mostly on the back of deep discounts. With the government capping discounts, the incumbents may now struggle to even retain existing customers.

At the time, though, it looked like Amazon and Walmart might be given an extension on meeting the new regulations. And besides, the newsletter was primarily about Amazon’s earnings statement. What were the odds a wonky regulatory skirmish halfway around the world was going to become big news for the world’s biggest retailer?

The odds were very good, it turns out! Amazon did not get an extension, it had to pull a huge number of its own products off its digital shelves, and all of this came up in an earnings call after Amazon gave lower-than-expected revenue and profit projections for the next quarter.

People with money in Amazon are counting on Amazon’s global growth. And India, in addition to being one of the biggest markets in the world, and specifically one of the most important to Amazon’s future plans, was also sending a broader signal that local governments and local retailers were not necessarily going to play nice when companies like Amazon and Walmart came to gobble up their business.

Now this has already been characterized as political posturing by India Prime Minister Nahendra Modi in an election year, and it certainly helps allies like Ambani, who’s India’s richest man.

Looked at another way, though, you could argue that India’s regulations are the first serious pushback against Amazon (and to a lesser extent Walmart/Flipkart’s) monopoly/monopsony power. A huge part of what makes Amazon a dominant force in retail worldwide is its ability to sell its own branded products, buy out local partners to do its bidding, and generally overwhelm the market with low prices on everyday goods. India is pushing back. The country’s politicians and many of its retailers don’t want what Amazon is selling. (Whether its consumers want it is another story.)

But Amazon’s grocery products are already being made available again, and financial analysts are already bullish on Amazon’s ability to find local partners (that it doesn’t indirectly own, which is how Amazon had gotten around India’s regulations before) to get its goods to market.

Mumbai-based rating agency CRISIL had projected that Amazon and Flipkart may lose up to 40% in revenue—between Rs35,000 crore ($5 billion) and Rs40,000 crore—by 2020 due to the new FDI norms.

But the sector’s growth is intact. At worst, it has been impacted only temporarily. Both Amazon and Flipkart are working out plans to hedge against the new rules. “The changes are happening as we speak, and they (e-tailers) will be back to full capacity soon,” an industry source told Quartz.

From the same report: India is adding 10 million daily active internet users a month. 10 million! That market is just too big for Amazon not to do what it has to do to comply or appear to comply with whatever regulations get thrown at them, and even play nice with the government.

There’s also still a strong sense in the world outside the U.S. that “Amazon is just a bookstore.” I got this a lot when people reacted to Kashmir Hill’s terrific essay about cutting Amazon completely out of her life. Sure, readers said, Amazon might be synonymous with the cloud in the United States, but here, it just isn’t so.

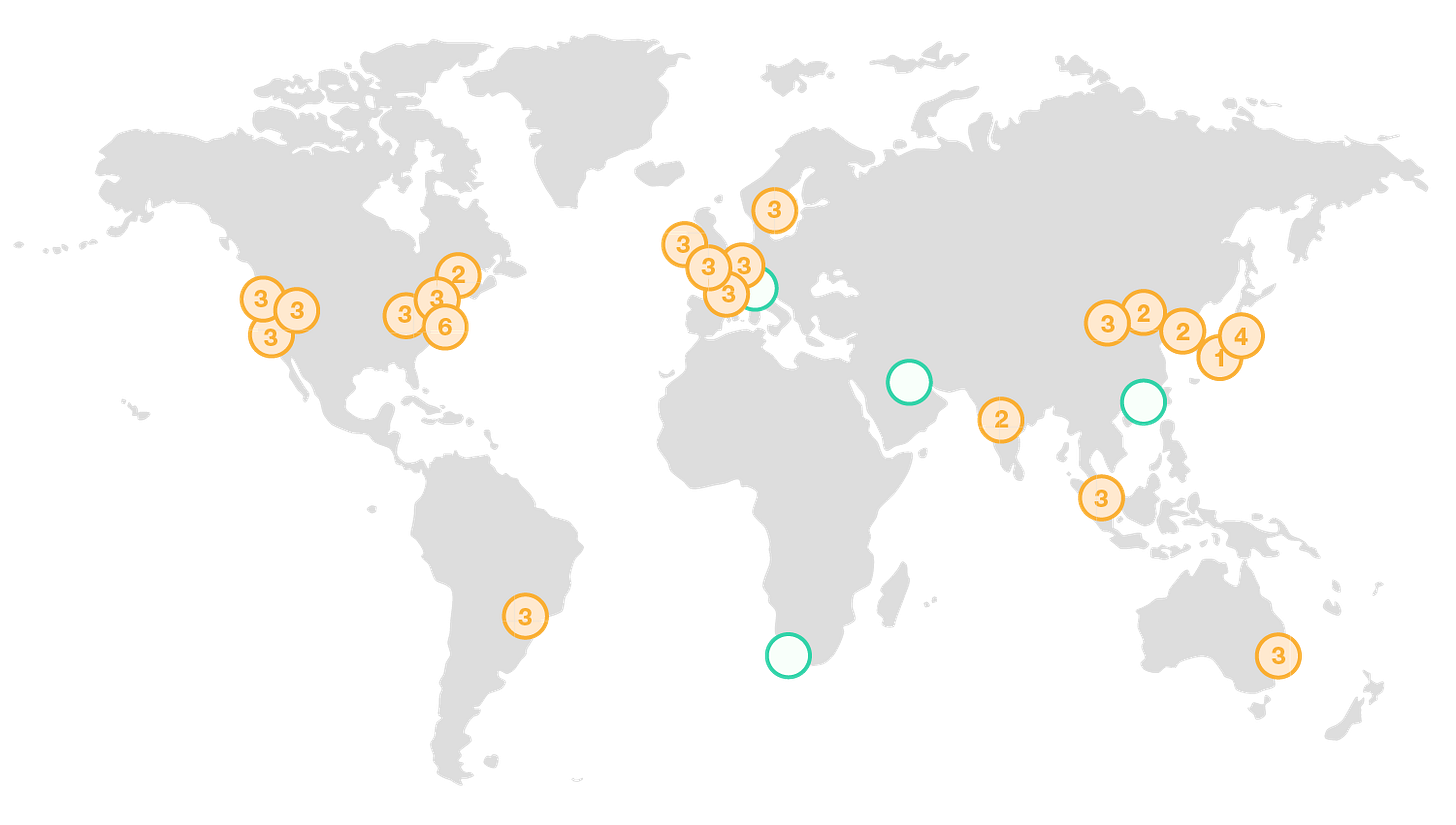

First of all, that’s not true. Here’s a map of AWS cloud centers:

Canadians, that “2” up there around Toronto is you. It’s been active since 2016, about as long as Amazon Prime has been streaming in India. Amazon’s global ambitions are total. It’s not going to be about selling discount groceries and cleaning products (as fine a business as that can be) for very long. It wants, at a minimum, to be the online retailer of full resort. And if it can control the cloud in your region, too? Well, that sounds to Amazon like an excellent start.

More Things to Read

Your Must-Read

This is a long one, but I promise you it’s good. Lina M. Khan’s “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox” from the Yale Law Review speaks to Amazon’s situation in India, the United States, and worldwide. It goes deep on legal history and theory, but it’s very accessible, and offers a compelling picture of where Amazon is right now, and how it’s been able (in the United States at least) to carve out such a dominant position without running afoul of antitrust laws.

In some ways, the story of Amazon’s sustained and growing dominance is also the story of changes in our antitrust laws. Due to a change in legal thinking and practice in the 1970s and 1980s, antitrust law now assesses competition largely with an eye to the short-term interests of consumers, not producers or the health of the market as a whole; antitrust doctrine views low consumer prices, alone, to be evidence of sound competition. By this measure, Amazon has excelled; it has evaded government scrutiny in part through fervently devoting its business strategy and rhetoric to reducing prices for consumers. Amazon’s closest encounter with antitrust authorities was when the Justice Department sued other companies for teaming up against Amazon. It is as if Bezos charted the company’s growth by first drawing a map of antitrust laws, and then devising routes to smoothly bypass them. With its missionary zeal for consumers, Amazon has marched toward monopoly by singing the tune of contemporary antitrust.

I actually pumped my fist when reading this. As I wrote for Wired in April 2012, “Jeff Bezos should send Eric Holder a Christmas Card” after Holder’s Department of Justice looked at what was happening in e-books, and basically concluded “low prices good, high prices bad” regardless of what was happening to pressure book publishers into making their products available at such low prices. (This is not to say that Apple and the publishing industry covered themselves in glory; just that Amazon was using its power as the dominant purchaser of e-books from publishers to push through some shady things as well.)

If reading an entire law review article sounds daunting, you should also check out The Verge’s Nilay Patel’s interview with Khan, where they talk about Amazon and Facebook. Here’s Khan’s TL; DR:

[T]he argument I made was that Amazon is a really elegant illustration of how the current framework in antitrust, the consumer welfare framework, really fails to capture forms of market power and forms of dominance that should be relevant to antitrust and do raise competition concerns. And so I was writing about Amazon because I think aspects of Amazon’s business strategy, specific practices that it used to become as dominant as it is, are a really useful vessel for talking about these broader shifts in antitrust. And so, you know, before I went to law school I was a journalist and a policy researcher and had spent some time interviewing the merchants that sell on Amazon. Just to try and understand it. You know, what are the business practices here? What are the contractual terms? What are the kind of day-to-day reality for these millions of merchants that feel dependent on Amazon, right?

They feel that the only way they can really get to market in the internet age is by using Amazon, by selling on Amazon. And then also by interviewing investors, hedge funds, venture capitalists to try and see how Wall Street was thinking about Amazon and the dominance it was amassing. Those perspectives, [the] kind of people who have money on the line and interacting with Amazon and how they see the company, really helped shape how I think about the company’s power. And then thinking about how these people were thinking about Amazon and then thinking about how current antitrust law perceives Amazon just revealed this gap. I was interested in exploring this back gap and interested in thinking about how antitrust should be reformed in order to reflect the new realities of how market power gets exercised.

If you want a super TL; DR, it’s this: Amazon’s practices have generally resulted in lower prices for consumers, but worse deals for literally everyone else involved. And Amazon has been able to get away with that because starting in the 70s and 80s, antitrust law shifted its emphasis from “is this structurally a monopoly?” to “how does this monopoly power hurt consumers?” As long as Amazon keeps delivering those low prices, he can’t be touched. In the United States! India and the rest of the world, however, are a different story.

And it that doesn’t work for you (or you’re just dying for more), there’s a new edition of KUOW’s terrific Primed podcast titled “Is Amazon to big to trust?” that cites Khan and Tim Wu in tackling this thorny issue of Amazon and antitrust law, plus the broader issue of our trust in Amazon, from retail to Alexa to AWS.

In this episode, we look at the Amazon Trust Matrix. (I think that’s what you called it, right?) (Yeah, I like it!) And that’s about how trust looks different if you’re looking at Amazon from a consumer’s point of view, versus if you’re looking at them from a vendor’s point of view, or a citizen’s point of view. (Trust vs. anti-trust.)

Amazon is the second most trusted institution in the United States, only behind the military. How did Amazon become simultaneously one of the most trusted and most distrusted companies in the world, in a time when we don’t trust government, business, the media, other tech companies like Facebook, or many other institutions? And how do both those feelings of trust and distrust get justified? I think this is the central contradiction at the heart of this company, and one of the reasons why it fascinates me so much. (It’s also one of the central contradictions at the heart of capitalism, but hey; why get ahead of ourselves? I’ll wait until we crack 1000 paid subscribers before this newsletter goes full Marxist.)

Alexa, what’s happening?

So, one of the things I’ve had to decide with this newsletter is what I’m going to cover and not cover. And essentially, I’ve decided that it isn’t my job to help Amazon sell anything. So you won’t get updates from me about hot Amazon sales, or discounted prices on Alexa-enabled products, or any of those things you can get from most gadget blogs. I’m not going to write about Amazon’s Super Bowl commercial. (I do write about the Washington Post ad below, because Jeff Bezos sickens and fascinates me.)

However, if Amazon is doing something cool or interesting on the software or hardware side, I am going to highlight that. And a lot of the cool and interesting things happening with Amazon software right now are happening with Alexa.

The Echo Dot was Amazon’s most popular device last year and is now sold out until March. People are buying these things.

Venture capitalist Benedict Evans had a much-read blog post about Alexa this week titled “Is Alexa working?” Basically, the fundamental problem is this: Amazon is in the business of selling things. Does Alexa actually help Amazon sell anything? Is it just marketing? Or is it a fundamental innovation in user interfaces that’s worth pursuing for its own sake? Here’s the upshot:

One of the fundamental shifts that came with mobile was that the users’ device became a lot less neutral. On the desktop, there were pretty narrow limits to what a web browser could do to control the economic models and interaction models of websites. On a smartphone, the management of everything from system permissions to default apps to notifications and interaction models (not to mention in-app purchase) means that Apple and Android are in much more direct control of what companies using these devices to reach customers can do. Ironically, a major reason why Google bought and built Android in the first place was fear of what Microsoft and Nokia might do with such power. Now Amazon is faced with this. The end point has become much more strategic for web platform companies. So, anything you can do to get an end-point of your own has value for the future, even if no-one today uses it to buy soap powder.

Does that actually answer the question? Kinda? I don’t know; this is a tricky issue, so I don’t totally blame Evans for punting on it. I think the other way you could approach it is to say that Amazon, through its advertising and web services businesses, is much less purely in the retail market than it used to be. So, all of the information it gobbles up through Alexa is hugely valuable in creating ads, establishing user profiles, gathering data on user habits, building up a natural language database, and so forth; basically all the stuff Google and Microsoft have done for years as a hybrid data-for-ads/data-for-research play. In that respect, Alexa represents a huge success for Amazon.

But what are people actually using Alexa to do? There are over 80,000 Alexa skills, most of which are doubtlessly terrible. If you’re full into the smart home revolution, Alexa can do a lot more for you than it can for other people. Myself, I have an Echo Show that I mostly use as a clock radio (although, being able to set and turn off alarms by voice really is game-changing) and an Alexa-powered Sonos speaker bar that mostly apologizes whenever someone says something that sounds vaguely like “Alexa” on television. (I know, I know; I let the surveillance machine into my home, and I’m a fool. I do it for you, so I actually know what I’m talking about when I write about this company.)

At Lifehacker, Emily Price spotlights how you can use Alexa to translate speech from other languages. Another new skill allows users to check their email using voice commands on Alexa devices, where Alexa can read your email out loud to you (it’s like Google Voice transcripts in reverse!). And Amazon itself touted its new API for keeping track of baby activities, for parents and other caregivers who want to quantify diaper changes, feeding times, and sleep patterns.

The big growth opportunity for all of these use cases (including maybe even the baby one?) may not be in your home but in your car, where voice assistants have several huge advantages over touchscreen interfaces.

Of those who’ve used voice assistants in their cars, 68 percent do so monthly. That’s compared with 62 percent monthly usage among smartphone voice assistant users. Smart speakers have the highest rate of voice assistant monthly usership—79 percent—but that’s not surprising as voice is the only way with which to communicate with speakers.

Amazon and Google—the two biggest names in voice technology—have taken note, with a spate of recent voice assistant offerings for the car. At CES last week, Google Assistant debuted on a couple of car devices meant to bring the voice assistant into automobiles. Amazon released an Alexa-controlled smart speaker for cars back at its annual hardware event in September. Extending its voice assistant to the car is particularly important for Amazon which, unlike Apple and Google, doesn’t have a smartphone.

The more comfortable people get with voice interfaces, and the more uniform their experience is across devices, from smart speakers to PCs to phones to cars, the more they’ll use them, and the bigger opportunity there will be for any company, whether it’s Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft, or anyone else, to create a new computing paradigm and new computing spaces.

I think the broader shift from graphical to conversational interactions with our machines, whether it’s through voice or text, in everything from Alexa to Slack, is going to be the story of computing for the next decade.

Media fantasies

I love fan fiction. Jeff Bezos attended the Super Bowl. This is what Matt Rosoff at CNBC wrote about it.

What if the world's wealthiest person was in Atlanta to lay the groundwork for Amazon taking over the NFL's Sunday Ticket deal from AT&T's DirecTV? That could be a dream come true for NFL fans everywhere, especially those (like me) who live in TV markets outside of where their favorite team plays…

What I'd like to see is for Amazon to take over, then negotiate with the NFL to blast apart the all-or-nothing bundle for out-of-market games, and instead sell them a la carte. I'd pay $20 every week the Seahawks aren't televised locally just to watch from the couch with my son. I'm sure many other casual football fans are in the same situation. The hardcore fans who need to watch every game to keep track of their fantasy players will still pay top dollar, but the NFL is passing up extra cash from people like me.

There’s not anything to this, really… but there’s not nothing either. Amazon would definitely be interested in getting a cornerstone sports deal with the NFL. They just added NBA League Pass to their lineup of à la carte channels you can buy with Amazon Prime. And there’s some talk that the NFL’s recent ratings problems coupled with digital growth might drive down the bidding for digital rights enough that it might make it attractive to a company like Amazon.

I was also struck by this post on Amazon’s Alexa Blog, detailing how to send Media Event notifications to users of a particular Alexa skill, which would be particularly handy at notifying users about new sports scores, big events, and sports on TV.

Imagine a major curling sports league that has a schedule of games throughout the year that are broadcast on various channels. Fans may miss seeing games since they do not know the schedule or forget the channel to watch. The league has all the events recorded in a text file called schedule.txt, with details on the event name, event date, and network. They want to keep their customers aware of the upcoming schedule.

schedule.txt

2018-12-20T13:00:00.000Z, "Owls at Badgers", "Speech Radio"

2019-01-25T13:00:00.000Z, "Otters at Swans", "Listen Channel"

2019-02-14T13:00:00.000Z, "Pandas at Tigers", "Voice TV"

2019-03-17T13:00:00.000Z, "Snails at Otters", "Stream Site"

…The league wants to provide the information via multiple ways to help their customers informed and engaged. First, customers can launch the skill to hear details about the next event, or they can enable notifications to receive automatic alerts about upcoming events one day in advance. The league has hired you to build a solution to solve both scenarios. You accept the challenge and roll up your sleeves to design and build a new voice-driven experience.

“Curling.” Sure.

Amazon 100 percent has eyes on this market, and is looking to come at it any which way it can.

Rosalind Brewer, Amazon’s newest director

Amazon named Starbucks COO Rosalind Brewer to its board of directors, which had previously been all-white. (Genentech’s Myrtle Potter had been a director from 2004 to 2009.)

Here are some other facts about Rosalind Brewer:

She grew up in Detroit and graduated from Cass Tech High School, one of the best public magnet schools in the world. (I was also born in Detroit, did not go to Cass Tech, but my uncle and grandfather did, so I feel a strong sense of pride in the place.)

She was trained as a chemist and started at Kimberly-Clark as a research technician before eventually becoming president of manufacturing and global operations. NOT SHABBY.

This turned into a VP/Senior VP/Executive VP job at Walmart and finally CEO of Sam’s Club, where until 2016, she competed neck-and-neck with Amazon in physical and digital retail every day.

She’s a logistics whiz who’s bound to make the company better. The only thing better than adding her to the board of directors would be if they hired her outright.

HQ2’s still got problems

State Senator Michael Gianaris of Queens (he actually represents the district where Amazon wants to build its second headquarters) just got nominated to an obscure committee called the Public Authorities Control Board, which has veto power over the deal. Gianaris opposes the deal, at least as it’s currently constructed.

While he has called the current deal “unacceptable,” he has also said he does not want to force concessions from the company, instead pushing to scrap the current development plan entirely and to start negotiations anew. His office has sent out fliers telling Mr. Bezos to “stay in Seattle,” but Mr. Gianaris said on Tuesday that he does not oppose outright the idea of Amazon coming to Queens.

Even ex-mayor, current plutocrat Mike Bloomberg came out against Amazon’s HQ2 plans: “the reason they came here was not the tax breaks they got, which I didn’t think they needed.” Bloomberg thinks Amazon is in NYC for the talent, both already in the city and brought to it by Cornell’s new tech campus on Roosevelt Island.

NY Governor Andrew Cuomo, who hates and is hated by all of these people, is floating going around the Public Authorities Control Board to get the Amazon HQ deal done. Which would be a power grab without much precedent, even in New York politics. It’s come to this.

Bezos Watch

Amazon founder/CEO Jeff Bezos, who owns the Washington Post, authorized buying a Super Bowl ad mourning slain journalists and touting the company’s continued excellent journalism.

Critics came from two ends on this. Emily Smith at The New York Post’s Page Six reported that the Washington Post ad was a last-minute fill-in after Bezos yanked a more expensive ad he planned to run for his spaceflight company, Blue Origin. Bezos was reportedly embarrassed because his girlfriend Lauren Sanchez had shot footage for the Blue Origin ad.

Other critics came from the Washington Post newsroom and union, who didn’t understand why the company was paying millions of dollars for a premium TV commercial when employees are still waiting for better family leave policies, among other worker benefits.

Officially, the Post was “thrilled” with the ad and its response, which made the advertising industry crap its own pants, as historically newspapers haven’t spent much money on TV ads. Take it easy, folks; I think this might be a one-time thing.

That’s it for this week. Thank you all for reading this far. If you liked this issue, please link to it on social media or forward it to a friend. If you loved it, please consider subscribing as a paid member. Or give someone you know a gift subscription! If you have other feedback, please let ‘er rip.

We’re still on a once a week schedule, but there may be a supplemental housekeeping issue later this week. I’m still fine-tuning exactly what I want this newsletter to be, but I feel closer to it every day, and that’s largely due to your encouragement and feedback. So keep it coming!

Tim Carmody

https://tim-carmody.glitch.me/